Introduction

Architecture should not be defined as taking into account the details of implementation, such as what type of database is used, the server that will be employed, or the specific communication protocols that may be utilized. Architecture is more about how the components of the software system are defined and being able to organize them in such a way that they do not cause significant problems in cohesion, coupling, and dependencies among them during the phases of development, deployment, operation change, and maintainability.

The general purpose of architecture is to create a schema and structure for the software system to recognize the most essential and important elements while deferring decisions on less relevant details until later, when more information is available. By postponing those details, it is possible to have time and better resources to make more informed decisions regarding the finer details of the system.

The architecture must support:

- The use cases and functional operation of the system

- The maintainability of the system

- The development of the system

- The deployment of the system

Use case and Functionality

Architecture must demonstrate that the use cases and intended functionality of the system are fulfilled at a high level. This means that the architecture should clearly display all use cases, illustrating the actors and the relationships between the components of each use case. It should visibly meet all requirements and be capable of accommodating new features or changes in requirements. If the architecture does not effectively represent the use cases, it becomes useless; it may be well-designed for maintainability and development, but it will ultimately fail to meet the expectations of clients and stakeholders.

Operation

Architecture must also be capable of identifying resource limits and the necessary performance to meet the system’s demands based on its use cases. For example, it should determine the maximum request limit that could occur and identify the resources needed to ensure the system continues to function if that limit is reached. Additionally, considerations such as allowed energy consumption, memory usage, or the supported baud rate must be taken into account. By considering these factors, it can also be determined whether there is a need for a method to extend system resources through upgrades like multiple processors, external memory, or threads.

Development

Architecture should also be defined based on the structure of the software team. For small software teams, where development and deployment can be straightforward, creating an architecture with sophisticated interfaces and dependency boundaries might cause more problems than solutions. However, for large development teams, defining complex system structures to minimize dependencies between developers and reduce conflicts in functional changes becomes a good architectural approach. It’s also important to consider whether the software team will grow or shrink over time, and the architecture should be able to adapt to or plan for such changes throughout the project’s lifecycle.

Deployment

Architecture should minimize reliance on numerous configuration files and complex deployment steps after the build process. The deployment should be as straightforward as possible, with any necessary variations being easy to understand and implement. For instance, if configuration settings are stored in a file, there should be a clear process for inputting these settings, along with a reliable verification mechanism. The inputs and outputs of this process should be intuitive and user-friendly. While deployment variations and methods may be inevitable, the architecture should aim to simplify the software’s interactions with these elements. The goal is to reduce dependencies and streamline the deployment process, making it more manageable and less error-prone. This approach ensures that the architecture supports efficient and reliable software deployment, even when accommodating different deployment scenarios or configuration requirements.

Architecture Principles

To fulfill these expectations, architectural principles can be applied, drawing from *SOLID** principles (Single Responsibility, Open-Closed, Liskov Substitution, Interface Segregation, and Dependency Inversion) along with other established design patterns, architects can develop systems that are flexible, modular, and easier to evolve over time.

Layers

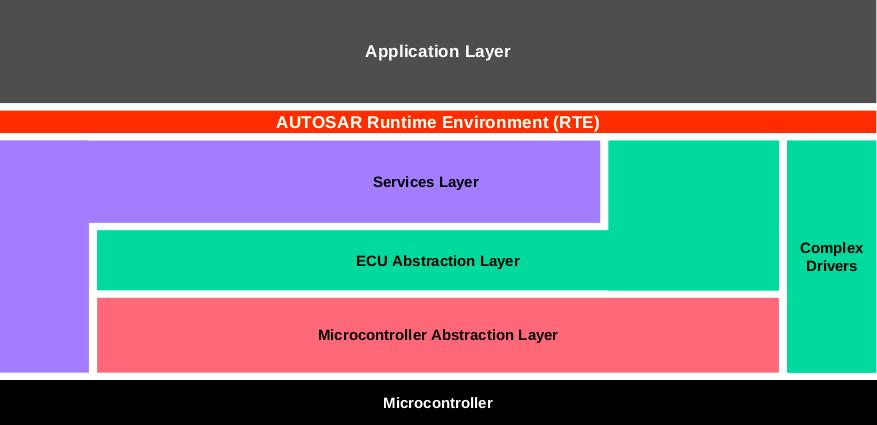

The definition of layers in software architecture is based on drawing horizontal lines across the system. The highest layers are those closest to the most prominent business rules or use cases identifiable by stakeholders/clients, with the application typically at the top. As you move downwards, there are layers of abstraction based on components with common interface types between horizontal layers. For example, below the application layer, there should be a component layer where interfaces can be defined as services and behave similarly. Intermediate layers can be more concrete abstractions and act as middleware between the service layer and the device abstraction layer. At the lowest levels are components where interfaces directly interact with low-level devices or hardware, such as drivers, I/O, communication buses, etc.

A notable example of this layered approach is the AUTOSAR architecture, which clearly demonstrates horizontal layers following the pattern described above.

Use Case

The definition of use cases is based on drawing vertical lines across the system architecture. These vertical lines represent unique use cases, spanning from the top to the bottom of the architecture description. Combined with horizontal layer lines, they help isolate and organize components, making them easier to identify. These vertical lines, often referred to as “stacks,” group components based on their functionality within the software system. For example, in Ethernet communication, the Ethernet stack starts with the low-level driver component, followed by the middleware interface for Ethernet, then moves to the service layer to handle request dispatches for Ethernet communication, and finally reaches the application layer use case. The primary purpose of this Ethernet stack is to ensure proper communication via the Ethernet protocol, focusing exclusively on components relevant to this functionality.

As shown in the image below, vertical lines represent these components (with only one horizontal line connecting to the Network Management component, which is irrelevant in this example).

Software Modes

This decoupling depends on factors such as inputs, the environment, the server, or the GUI used for deployment. For instance, the architecture may need to separate servers with higher resource demands and faster performance from those with lower resource requirements. This principle applies to any configuration or paradigm at the operational level.

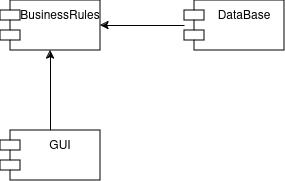

Business Rules as pillar

Business rules are independent of any GUI, tool, database, or other components represented in the architecture. This is because business rules form the backbone of the software’s purpose or intent, while the GUI serves as a means to present that backbone, and the database functions as a tool to store and retrieve data for it. Consequently, a well-designed architecture will always show dependencies leading to the business rules but never from the business rules to other components. For example, the GUI and the database depend on the business rules to function correctly, and without the implementation of these rules, neither the GUI nor the database can operate as intended.

Boundary Strategies

A boundary strategy can involve source-level decoupling, service decoupling, or local processing decoupling. The choice of strategy depends on the specific use case and the acceptable trade-offs in terms of time and memory consumption.

Source Level Decoupling

Within the same processor, task, and address space, source-level decoupling relies on function calls as boundary interfaces, which are highly efficient in terms of execution time. These boundary interfaces remain consistent whether used in a simple executable or a deployed component with libraries, as the function call operates the same regardless of where it is allocated in memory—provided it remains within accessible memory boundaries. In source-level decoupling, the trade-off lies in the need for careful architectural analysis to prevent unwanted dependencies between interface calls across components. This often involves leveraging component abstractions to invert dependencies, ensuring they do not align with the program’s control flow. Achieving this typically requires the use of architectural patterns such as factories and interface-implementation patterns.

Local Processing Decoupling

Local processing decoupling relies on the use of independent tasks or processes, each operating in isolation. This independence is achieved by assigning specific memory addresses exclusively to each task, ensuring that the memory is protected and accessible only by the designated task. Boundary interfaces for local processing can include shared memory, sockets, mailboxes, or message queues.

Service Decoupling

Service decoupling is the most time-intensive of all boundary strategies but also the most robust. It operates over a specific network and relies on boundary interfaces, such as request-response mechanisms.

Policies and Level

Policies are rules derived from use cases that help identify their relationships and hierarchical levels within the system. The level of a policy is determined by its proximity to the system’s inputs and outputs. Policies farther from inputs and outputs are associated with more stable components, making changes to them more significant. In contrast, low-level policies, closer to the inputs and outputs, are more prone to frequent changes but are less critical. High-level policies can be viewed as the business rules or core components of the architecture, which should be kept as stable and abstract as possible. Meanwhile, low-level policies require minimal focus and are primarily concerned with handling specific input-output operations.

Entities and Use Cases

Critical business rules are essential policies that ensure a business saves or earns money. These rules operate at a high level and are independent of specific use cases or the software’s implementation. A key characteristic of critical business rules is that they can be executed either by software or manually. They can also be performed by individuals or through other methods. Critical business rules rely on specific inputs, known as critical business data, which directly influence their operation.

In software, these rules can be represented as objects, where the inputs are the critical business data and the outputs serve as interfaces for lower-level policies. These objects are referred to as Entities. Entities represent the highest-level abstraction of critical business rules in software.

Below this level are Use Cases, which, while not as abstract as entities, remain independent of system-specific details to some extent. However, use cases have a closer dependency on how an application manages the execution of these rules. This is because use cases often involve entities constrained by business requirements that the application enforces. Essentially, use cases define how software saves or earns money by leveraging its ability to manage and apply critical business rules effectively.

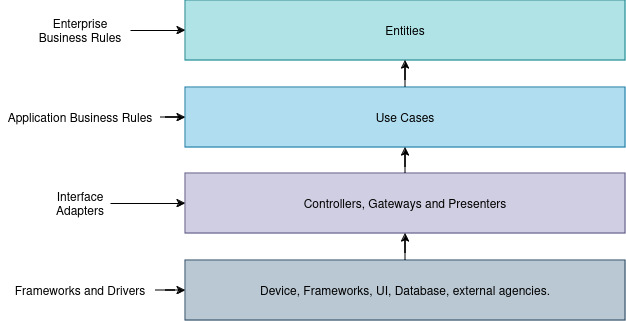

Dependency architecture

An architecture must identify the components and their types, focusing on ensuring that business rules and use cases remain independent of the UI, database, or any external agency, while also being testable independently of these external components. Thus, the following image will aid in understanding how these dependencies are structured.

Dependency arrows will always point toward higher levels, never the other way around. Entities will never depend on use cases or frameworks to remain functional and testable. This ensures that entities can be tested early in the project and later integrated with any framework or database without being tied to them. Since entities are independent of lower-level components, any changes or bugs in those components will not impact the higher-level entities. Similarly, use cases depend on entities, meaning changes to entities can affect use cases. However, use cases do not depend on gateways or drivers, ensuring that bugs in these lower-level components will not impact the functionality of the use cases.