Component Diagram

A Component Diagram illustrates the relationships between software components. When representing a component on the diagram, you can use a «component» title, a software component icon, or both to visually convey the nature of the component within the system. This notation aids in clearly depicting the structure and connections among various software components in the system architecture.

Ports in a Component Diagram are square shapes positioned on the boundary of a component, and they play a crucial role in defining the interaction of the component with its environment. These ports can have visibility attributes, appearing as “public” when the square is located between the interior and exterior of the component, and “private” when the square is entirely contained within the component. This distinction helps to specify the accessibility and visibility of the component’s interfaces with the external environment.

In the notation of services within a component interface, a symbol referred to as a socket/ball is used. A ball signifies the functionality that the component provides to the external environment, while a socket represents a functionality that the component requires from the external world. In cases where there are numerous interface ports, they can be grouped to showcase common interfaces, providing a more organized representation on the diagram. This grouping helps manage the complexity of illustrating a large number of interface ports within the component diagram.

When a component is complex (it contains several components within it), it is called a subsystem and should denote «subsystem» instead of «component».

If more detail of the interfaces is needed, the following notation can also be used:

Package Diagram

A Package Diagram in UML is a structured diagram that depicts dependencies between packages. In this context, a package serves as the fundamental representation of various model elements, such as classes, software components, software units, and more. Due to its abstract and high-level nature, packages are valuable for partitioning use cases or defining groups of software component deliveries. Package Diagrams provide a visual means to understand and communicate the organization and relationships among different elements within a system or software architecture.

The notation of the package is as follows: (+) means that the package is public. (-) means that the package is private.

The dotted arrow with an open arrowhead means “dependency”. The tail is located to the element having the dependency, and the head is located to the element that supports that dependency.

In a Package Diagram, arrows can be labeled with “«»” to emphasize the type of dependency between packages. Three common dependency types used in package diagrams are:

- «import»: Represents a dependency where elements of one package are utilized in another package without necessarily having a direct relationship. It indicates that the target package incorporates elements from the source package.

- «access»: Signifies a dependency where elements in one package access the contents or functionality of another package. It denotes a more direct interaction between the packages.

- «merge»: Indicates a dependency where two packages are combined into a single package. This implies that the contents of the packages are merged, and they function as a unified whole.

These labels help in clarifying the nature of dependencies between packages and enhance the understanding of the relationships in the diagram.

The disclosure of dependency types is as follows:

- Import: Grants permission to a package to access the content of another package and introduce aliases to the names based on the importer. This is akin to a “public” import, as it involves referencing public items in the package being imported.

- Access: Provides permission for one package to access the content of another package. It is more accurately described as a “private” import, as it involves accessing private elements within the package being accessed.

- Merge: Allows one package to integrate the content of another package into itself. This signifies permission to combine and intermingle the contents of both packages.

Package partitions play a key role in organizing systems based on architecture layers. This organizational approach proves beneficial for subsequent diagrams such as use case diagrams and subsystem specifications. When transitioning from package diagrams to use case diagrams, it is advisable to maintain the integrity of the dependency relationships without breaking them.

An indicator of good package design is when there are more interactions within a package than between external packages. This signifies that the components within a package are well-connected and collaborate effectively, promoting a cohesive and modular design. It reflects a design where the internal cohesion of packages is strong, contributing to a more maintainable and comprehensible system architecture.

Class Diagrams

Relationships.

In UML, there are different ways to define relationships between two classes, including:

- Composition: This is a strict relationship where an object A (arrow origin) composes another object B (filled diamond), and object A cannot exist independently of object B. In C++, this is typically implemented by having a container of objects A within object B and ensuring that the creation and management of objects A are exclusively handled by object B.

- Aggregation: This is a less strict relationship than Composition, where an object A (arrow origin) is aggregated into object B (empty diamond), but object A can exist independently of object B. In C++, this often involves having a container of objects A in object B without restricting the creation or management of objects A.

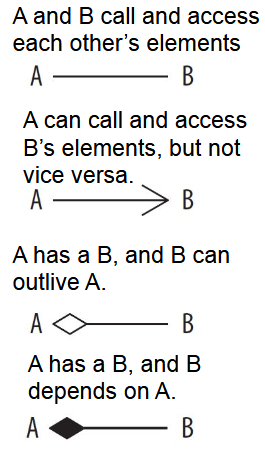

- Association: This is the most flexible type of relationship, where objects are aware of each other for specific purposes but do not impose any ownership, management, or restrictions on one another. When the line between two classes does not include an arrow, it indicates that both classes have mutual access to each other’s elements. However, if the line includes an arrow pointing to class B, it means that class B does not have access to the elements of class A, while class A can access the elements of class B.

In UML diagrams, you can define restrictions on the number of objects that can be in a relationship, which is referred to as cardinality. Cardinality specifies the minimum and maximum number of instances involved in the relationship. For example:

- 0..*: This means “zero or more” objects can be associated.

- 1..1: Exactly one object is required.

- 1..*: At least one object is required, but there can be many.

- m..n: Specifies a range, where at least m and at most n objects can be associated.

If an asterisk (*) is used, it indicates an unlimited number of objects. Cardinality is typically displayed near the ends of the relationship lines in UML diagrams to clarify these constraints visually.

Another property of relationships in UML is navigability. Navigability specifies the direction in which a relationship can be traversed and is represented by visual indicators such as arrows or diamonds. It determines whether one class can “see” or access the other class in the relationship. Navigability can take the following forms:

- Unidirectional: The relationship can be navigated in only one direction, meaning one class knows about the other, but not vice versa.

- Bidirectional: Both classes are aware of and can navigate to each other.

- Self-directional: A class has a relationship with itself, allowing navigation within its own instances.